|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

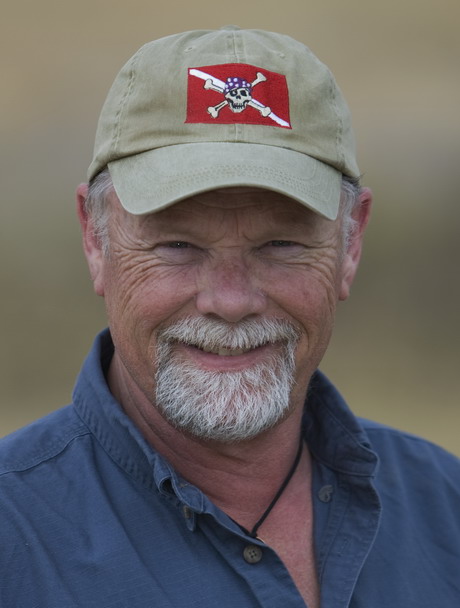

Aggression and Operant Conditioning By Gary Wilkes Copyright 2009 About 30 years ago I was attempting to give a fatal injection to a Lab mix. I was new at the job and a little hesitant with presenting the needle. As the needle kissed his skin, the dog jerked his foreleg back and tried to bite my hand. As he lunged, the syringe slipped from my fingers. By complete fluke, at the instant the dog’s teeth tried to close on my hand, the syringe was balanced on the table, pointing straight up. By trying to bite my hand, the dog inadvertently stuck himself in the lip with the needle. A behavior analyst would say that the lunging behavior was contiguous with the presentation of an aversive stimulus that likely constituted a positive punishment procedure. That is a lot of words to simply say that the dog punished himself accidentally. Regardless of how you describe it, he recoiled backward exactly as if he’d been jabbed in the lip with a 20 ga. needle. Now I was faced with a dilemma. I was less than confident about my ability to euthanize this dog. I mustered up all my courage and put a fresh needle on the syringe. As I placed the needle along the cephalic vein, I plainly saw the dog flinch. As the needle entered the skin, I saw something else. At the instant that mirrored his attack on the last repetition he clearly pulled his head backwards. He was attempting to avoid the needle that wasn’t there. By any analysis, the bite of the needle stopped the bite of the dog on the first occurrence and created a latent inhibition against biting on the second repetition. This is a perfect example of controlling aggression with an operant conditioning procedure. Reality Check It is a common in modern training and behavior philosophy to assume that aggression is a sacred mystical phenomenon that cannot be directly confronted. Often the fundamental aspects of aggression are side-stepped through a process of naming all the various triggers for aggression – dominance aggression, food aggression, predatory aggression, territorial aggression and a host of “aggression du jour” categories. This is like asking someone how to make ice-cream and they instead offer a list of flavors. That doesn’t answer the question. Dividing aggression into myriad subcategories merely tells us the context of the behavior. Unless treatment is different for these various types there is no need for the classifications. One wonders the purpose of telling a client that their dog has “resource guarding issues” after the dog bites to defend a treat. It is doubtful the owner needs that information or the task of learning a fancy term In reality, there are only two forms of aggression – the kind you can stop and the kind you can’t. A behavior analyst might term this operant (controlled by its consequences) vs. non-operant (not influenced by consequences) aggression. The problem is that modern experts do not know how to stop behavior. That is because they openly vow never to use the tools that can actually stop a behavior. Current Practice: More Experience to Ponder: About 25 years ago I was working with an Australian Cattle Dog named Molly and a Terrier mix named Punkie. They were both fully adult females and had a short but violent history of aggression. The younger dog, Molly, was reaching social maturity at about 18 months of age. The older dog, Punkie, was about three and fully mature. This is a common scenario for inter-female aggression. Molly, the Cattle Dog, was a very tough animal. She had received very damaging wounds from the collective fighting with no lessening of her will to attack. During one fight her jugular vein was exposed. Punkie, though technically a poodle-terrier, resembled the poodle only by the texture, length and curl of her coat. Under the skin she was a barrel-chested Jack Russell. My then na´ve self followed the contemporary and still “modern” goal of using primarily positive reinforcement to solve the problem. All of the books I had read suggested that punishment isn’t effective in stopping aggression. It was universally promoted that “science” confirms that positive methods are superior to punishment. (NOTE: Science doesn’t confirm nature. At best, science describes nature accurately. If nature contradicts science, the “science” is flawed, as in this conjecture.) The slogans attached to the topic were compelling: violence begets violence, punishing aggression merely punishes the symptoms without stopping the actual behavior, punishment causes rebound aggression and alienates the animal from the owner/punisher. To avoid these dire consequences I crafted a subtle, brilliant and utterly stupid solution using positive reinforcement. I taught Punkie to wag her tail, on command. One of the triggers for the dogs’ fighting was Punkie’s tail carriage and movement. Her tail carriage was typically terrier – straight up, high over the back and flagging – a sign of aggression in most breeds and more specifically, a sign of aggression to Molly. Cattle Dogs, by contrast, stand comfortably with their tails pointed at the ground. When a terrier has its tail over its back, it’s a normal posture. When a Cattle Dog elevates its tail, it’s a threat. Molly felt constantly threatened by Punkie. As a first step toward fixing the problem I decided to use positive reinforcement to weaken one of the triggers. I taught Punkie to wag her tail on a horizontal plane rather than hoist it up over her back. As I envisioned the process it worked brilliantly. When the owners noticed Molly bristling over Punkie’s tail, they commanded “wag.” Punkie would dutifully drop the elevation of her tail and twitch it back and forth in a traditional wagging pattern. Boy, I thought I had a brilliant solution. In reality, it was a stupid waste of time because it did nothing to actually inhibit the aggression. Punkie’s overly-muscled rear-end made it impossible for her to maintain a wagging pattern for more than about 20 seconds. After her muscles fatigued her tail gradually elevated above her back into a perceived threat. More importantly, positive reinforcement doesn’t cause an inhibition that would carry into the future. Unlike my lab-mix who withheld the bite on the second experience with the needle, neither Punkie nor Molly were in any way inhibited from either high-tail carriage or major throat ripping in the future. My solution was missing the key ingredient because I believed “experts” who really weren’t. We Meet the Bottom Line: As I yelled “NO!” both dogs froze for a split second. My preconditioning with the water bottle had at least achieved that. As my mind ruled out throwing my hard-sided brief case at them, I looked down at the couch in front of me and found the solution -- I picked up a throw pillow and allowed it to live up to its name. The pillow grazed the hair on Punkie’s back and hit Molly right between the eyes with some force. She spun around and ran down the hallway, submissively wetting the whole way. She went under a bed and couldn’t be persuaded to come out for more than 30 minutes. I said to myself…”Hmmmmm.” According to all the experts, what I had just done couldn’t have happened. There was no rebound aggression. The dogs didn’t perceive the throw pillow as a participant in the fight. They didn’t explode into battle as it hit them. After the fight, no aggressive overtures occurred for more than two weeks. (Prior to the “bonk” they were fighting daily.) Neither of the dogs hated or feared me after the incident. Neither dog was at all harmed by the process. They obviously benefitted from the end of violence. This process defied conventional scientific wisdom. A New Day Dawning: I was chagrinned to realize that the key to effectively using punishment is a mirror image of the key to using positive reinforcement. Click, then treat is the mirror opposite of creating a marker signal for punishment followed by a punishing stimulus. i.e. Say NO!, then apply the tangible behavioral effect. (In this case, a thrown pillow) Soon, I integrated precisely applied positive punishment to aggression despite the virtually unanimous warnings against its use. I discovered that some forms of aggression are very sensitive to operant conditioning. Food aggression, for instance, can be stopped with an almost 100% assurance of success – if you know what you are doing. If you believe it can’t be done, you will never gain the experience to know how to stop it. After using positive punishment on more than 7500 dogs, I have only seen three cases of rebound aggression – all directed at the “bonker” rather than a human. In some cases, a single experience of properly applied punishment can stop a dangerous behavior for a lifetime. In other cases, more lengthy procedures must be used, often including an in initial punishment procedure followed by positive reinforcement for correct behavior. (NOTE: The anti-punishment crowd always demand 100% solutions before they will entertain any discussion of using punishment. Animal behavior is a dynamic process that deals with individual animals who may be unique and may not respond to any form of treatment. If you are waiting for utopia before you attempt to save lives, you are in the wrong business. Additionally, those who oppose punishment unless it can be 100% effective with no side effects offer solutions that are based in a logical contradiction. Positive reinforcement cannot stop a behavior or inhibit its future return. That is because by definition, positive reinforcement increases behavior. It can’t stop anything. Meaning their “solution” isn’t effective at all. The harmful side effects of trying to use positive reinforcement to “stop” aggression is more aggression and usually devastating injuries and death. i.e. They do not hold their own “non-solutions” to any standard of efficacy. In every contest of ideologies you will find this mantra - attack the opponent for less than perfect results while offering nothing of substance as an alternative. ) The use of punishment and its complimentary opposite negative reinforcement to control aggression is a viable option for serious professionals. The inevitable result of inadequate treatment for this problem is injury to a human or other animals and death to the aggressive dogs. In essence, the behavior is almost always lethal. In medicine, the treatment is always evaluated in terms of the risk of not treating the ailment vs. the risk of the most likely successful treatment. In behavior, this is not so. The difficulty of discussing aversive control, rationally, is a long-standing and illogical bias against the use of aversive control within the behavior analytic community, behavioral psychology, veterinary behaviorism and now, mainstream dog training. Reports of failure or dire consequences using these tools appear to me to be the result of failed methods, improper application or a blind devotion to a flawed ideology. (By the logic of “positive” trainers, one cannot clip a dog’s toenails because it might cause pain and fear if you accidentally cut into the quick. Veterinary care is cruel and immoral because vets cause pain and fear as a regular part of what they do.) As there is no course, textbook, instructor, practical training, internship or certification within academia or veterinary schools to teach the correct use of punishment, this is undoubtedly the case. Instead of developing better procedures, as was done in the dawn of surgery, behavior experts wish to drown the baby in the bath-water. Using proper respondent and operant methodology opens up treatment to a large percentage of aggressive dogs normally assumed to be unfixable. To quote the Romans, abusum, non tollit usum – the abuse of a tool is not an argument against its proper use. BIG NOTE: In reality there is a good deal of scientific research that confirms everything I have learned. It is generally suppressed by people with academic degrees who coincidentally benefit by elevated status, tenure, cash and prestige by claiming to be experts on a topic they know nothing about, while prescribing drug therapies that do not actually control the behavior and have never been tested in blind trials against effective behavioral treatment. There is currently no course, text, instructor, practical training, internship or certification within academia that would qualify someone to use punishment. So, where did they get their status as experts? They made it up by repeating the claims and statements of other ideologues. The proof of that statement is easy to find. You can find the smoking gun by doing a full reading of the scientific literature. Here it is - Ulrich, Wolfe and Dulaney, Punishment of Shock Induced Aggression. Journal of the Experimental Analysis if Behavior. 1969. (It’s on line. Just do a google search of the authors and title.) They triggered aggression with electric shock. Then they stopped it the same way. They use the phrase “completely suppressed.” You can find a wealth of citations and a rational review of the topic by reading “The Effects of Punishment on Human Behavior” by Axelrod and Apsche. You can also find logical objections to the myths surrounding positive reinforcement by reading The Negative Effects of Postive Reinforcement by Michael Perone PhD. If a rational person did a full reading of the literature they’d come to the conclusion that the best tool for stopping aggression is a remote shock collar. That’s how scientists did it. The same scientists who created “learning theory”. The same scientists who created the literature that anti-punishment ideologues use to justify they withholding of treatment known to be effective. i.e. Real science confirms that aggression is not a mystical hands-off, “give them treats” behavior. It can be stopped. You do have to know what you are doing, but it’s learnable. As I said, if you don’t stop aggression the animal most likely dies. I do not believe in “Death Before Discomfort.” I choose life.

|

||

|

Copyright 1994-2013 Gary Wilkes. All rights reserved.

|

||